As the economy continues to worsen and as average American families encounter more difficulties trying to make ends meet, two “social trends” that have been constant through these recurring cycles of bust and boom are that (1) getting a good education is crucial to social mobility and financial security and (2) each succeeding generation has been able to improve their rates of getting a college degree.

But now, as Inside Higher Education reports, new data from the American Council on Education shows that perhaps for the first time in American history, some racial groups may actually be doing worse then their predecessors in terms of achieving a college education:

The latest generation of adults in the United States may be the first since World War II, and possibly before that, not to attain higher levels of education than the previous generations.

While White and Asian American young people are outpacing previous generations, the gaps for other minority groups are large enough that the current generation is, on average, heading toward being less educated than its predecessor. . . .

For Black and Latino women, for example, the most recent generation outperformed the prior ones, but the opposite is true for men. And across racial and ethnic groups, women are achieving a higher educational attainment than men.

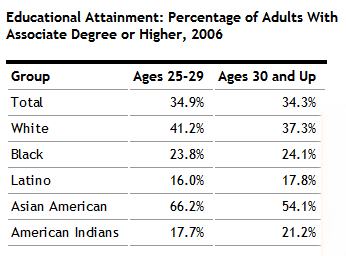

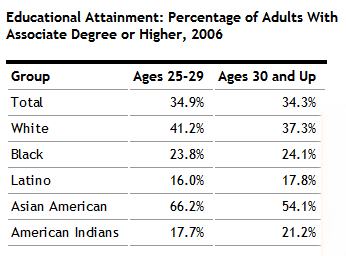

To summarize, the data basically show that comparing the percentage of adults with at least an associate’s degree, younger Whites and Asian Americans (those between 25-29 years old) had slightly higher attainment rates than their older counterparts (those who are age 30 and older), and this corresponds with the long-established trend that succeeding generations improving their educational attainment rates over previous generations.

However, the opposite seems to be true for African Americans, Latinos, and Native American Indians — those in the younger group have lower educational attainment rates than their older counterparts, which means the younger generation seem to be falling behind the older generation.

The data also shows that across all racial/ethnic groups, women have higher rates of having at least an associate’s degree than men.

So what are some possible reasons behind this trend of African Americans, Latinos, and Native American Indians falling behind, in contrast to Whites and Asian Americans? It may be tempting, especially among nativists and those who are racially ignorant, to say that these three minority groups are less qualified, motivated, and/or intelligent enough to complete college and attain social mobility.

However, the rest of the Inside Higher Education article provides more details for us to understand this situation more fully. Specifically, the article also notes that high school graduation rates for these three groups of color have remained constant over the past two decades (even though they still trail that of Asian Americans).

Further, the article notes that “Total minority enrollment increased by 50 percent, to 5 million students, between 1995 and 2005.” This tells us that after graduating high school, Black, Latino, and Native American Indian students are still entering college in large numbers.

So the problem seems to be, once they get into college, somewhere along the line, these minority students are not able to complete their associate’s or bachelor’s degrees.

Is it because they are unprepared for the academic demands involved? That is one possible reason. But more likely, and as other studies have suggested, since these three racial minority groups tend to be less affluent than Whites or Asian Americans, the main reason may be that as college expenses keep skyrocketing, these students eventually are unable to afford completing their college education and are more likely to drop out of college because of lack of finances.

As other studies also show, there are still gaps at many colleges in terms of racial inclusion — cultivating a welcoming atmosphere and social environment in which students of color feel supported and secure:

Intolerance, threats and verbal insults pervaded the campuses of three predominately White institutions, the University of California, Berkeley, Michigan State University, and Columbia College, according to a student survey in the recently released report, “If I’d Only Known.”

The report reveals that more than 60 percent of students at MSU reported witnessing or personally experiencing such incidents of violence based on intolerance, followed by 49 percent of students at UC Berkeley and 43 percent of students at Columbia. . . .

Research shows that comfortable environments play a major role in minority persistence. Scholars agree that isolation and racial violence contribute to the high minority drop-out rates at some institutions.

Ultimately, this trend of Black, Latino, and Native American Indian students beginning to fall behind their older counterparts in terms of educational attainment involves many factors. While some reasons undoubtedly relate to individual abilities or motivations, as studies continue to show, there are still many institutional inequalities and barriers that make it more difficult for these students to complete their degrees.

Whatever the causes, this is a disturbing trend that all of us as Americans should be concerned about.