April 30, 2015

Written by C.N.

40th Anniversary of the Fall of Saigon: Reflections from a Former Refugee

Today, April 30, 2015, is the 40th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon, the day when the North Vietnamese officially overthrew the South Vietnamese government and ended the Viet Nam War. As summarized in more detail in my article “A Modern Day Exodus,” most immediately, the Fall of Saigon led to a series of events that resulted in the hurried departure of over 125,000 Vietnamese out of the country to be eventually resettled into western nations such as the U.S. For a detailed historical summary of the Fall of Saigon, I highly recommend the documentary being shown this week on PBS stations all across the U.S., the Last Days in Viet Nam.

My family was among those who left Viet Nam in this first wave of refugees in the days immediately after the Fall of Saigon. I would like to share a few memories and reflections on this occasion and relate it my life in the U.S. now, and what my life likely would have been if I had stayed in Viet Nam.

The Journey Out

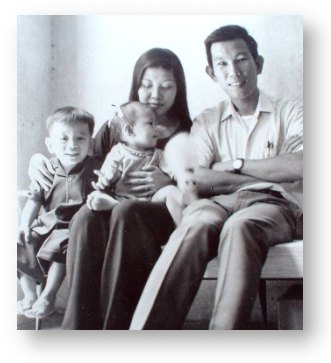

I was only five years old around this time. People frequently ask me what it was like back then and back there, and I always tell them the same thing — I had no idea a war was going on. The few memories that I have of that time were all very happy and normal ones — I remember going to the zoo with my parents, traveling into the countryside to take pictures with my dad and his friends on the weekends, and riding around with my dad on his motorcycle (to the right is a portrait of me, my little sister, mom, and dad from 1973). Fortunately or unfortunately, I have no memories of our departure out of the country, so what I am about to describe is what my parents have told me through the years about our exit from Viet Nam.

Both of my parents had worked for the South Vietnamese military, and in close conjunction with the U.S. military up until the Fall of Saigon. After finishing his education as a Structural Engineer, my father enlisted in the South Vietnamese Army Corps of Engineers and several of his first projects involved working closely with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. After five years, his tour of service was complete and he left the army and eventually opened his own engineering firm in Saigon. My mother started working for the South Vietnamese government and U.S. military as an office clerk (her brother Trang, also an engineer, worked with my father and eventually introduced them to each other).

After a few years, she eventually was promoted to writing radio propaganda programs (the “Voice of Freedom” program, eventually renamed the “Voice of Mother Viet Nam”) for South Viet Nam that were broadcast throughout the country. She was still working at this job right up to the Fall of Saigon. In these capacities, both of my parents would have been obvious targets for retaliation and punishment by the North Vietnamese had they stayed in the country. Fortunately, her South Vietnamese and U.S. employers arranged for our family’s exit out of the country by first evacuating us to the island of Phu Quoc, located off the southwestern coast of Viet Nam and about 100 miles west of Saigon, a week before the Fall of Saigon.

The North Vietnamese forces officially toppled the South Vietnamese government and took over the country on April 30, 1975. They issued a public announcement that said all U.S. personnel and their South Vietnamese allies had 24 hours to leave the country. After this announcement, panic and chaos ensued as our family and the hundreds of other Vietnamese families on Phu Quoc with us tried to arrange passage off the island and onto any U.S. vessel that would take us out of the country. Later that night, a cargo ship was dispatched to pick us and all the other evacuees up from Phu Quoc island. But we needed a way to reach that cargo ship located in the Gulf of Thailand. Eventually, we and other evacuees were able to board a small fishing boat and set off toward the cargo ship.

My uncle Trang’s family (my mother’s brother, who introduced my mom and dad to each other) were also with us on Phu Quoc, since he had worked for the South Vietnamese government as well. The plan was for all of us to stay together and to leave the country together. However, in the confusion of the moment, my uncle decided that he needed to try to secure some food for everyone before we boarded the cargo ship, so he kept his most of his family behind while he got a loaf of bread from one of the local villagers. Unfortunately, after he returned to the beach, all of the fishing boats had left. He and his family were now stuck and left behind on Phu Quoc.

My grandmother (my mom’s mother) did leave with my family on one of the fishing boats. Once our fishing boat neared the cargo ship, there was a “traffic jam” of dozens of other fishing boats and hundreds of other Vietnamese who were also trying to board the ship. The only way to get closer to the cargo ship was to jump from boat to boat. In the process of doing so (also remembering that this was in the middle of the night), our family got separated from our grandmother. Our grandmother was not physically mobile enough to jump from boat to boat, especially after the boats began drifting away from each other. Unfortunately, she was also left behind after everyone left and no one was around to help her.

Although my family had successfully boarded the cargo ship and were now on our way to the Philippines to eventually be resettled in the U.S., both of my parents were in shock and traumatized over losing first, their homeland, the country of their ancestors. Second, they (especially my mother) were traumatized that many of our loved ones, including her mother, brother, and brother’s family, did not make it out of the country and were left behind and in my brother’s case, would ultimately be singled out for punishment and sent to one of the notorious “reeducation” camps.

Connecting the Past and the Present

It would be more than 20 before my parents were able to return to Viet Nam and to see their relatives again. Unfortunately my mom’s mother had passed away in the meantime and my mom was never able to see her again. Nonetheless, in the intervening years, we did everything we could to send money to my uncle’s family, support them to achieve a comfortable, middle class standard of living, and sponsor them to immigrate to the U.S. One of my dad’s brothers received a visa and immigrated to the U.S. about 10 years ago. But for various reasons, no one in my uncle’s family has been able to immigrate to the U.S.

In our case, because both of my parents were relatively well-educated and proficient in English, they were able to get relatively good jobs soon after we were resettled in southern California. After just two and a half years, we were able to save and borrow enough money to buy a house in the suburbs and take a big step toward achieving the American dream. As I reflect on the past 40 years, I am very thankful to have gotten out of Viet Nam, to become an American, and to have access to the kinds of social and economic opportunities that billions of people around the world can only dream about.

One of those billions is my cousin Bao, the only son of my uncle Trang (the one who made the fateful decision to get a loaf of bread at Phu Quoc). He and I were born only six months apart and growing up in Viet Nam, we were basically brothers. Bao is now married with three young children. With his parents, he has been able to achieve a comfortable middle class lifestyle. He’s even been able to buy two cars in recent years. Nonetheless, he has been, and continues to be, desperate to leave Viet Nam in order to give his children a chance at a better life.

As I compare my life with his on this 40th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon, I can’t help but think that I easily could have been in his place. I easily could have been the one left behind while he was successful in boarding the ship to leave the country. I easily could have been the one to have suffered and been punished by the North Vietnamese. I easily could have been the one thinking that I and my family have no future as long as we stay in Viet Nam. I know that there are plenty of injustices and inequalities that I and others like me face in the U.S., but I cannot escape the fact that, compared to my cousin Bao, I am a very fortunate person to be where I am.

My cousin Bao recently told me that he is making one last ditch effort to leave Viet Nam by paying a labor recruiter to get him a job in the U.S. doing manual labor at a meat processing plant somewhere in the Midwest. If this employer is able to obtain a Labor Certificate for him (in which the employer can document that there are very few American workers available and willing to work in this job), supposedly Bao would be able to take his entire family to the U.S. while he works for at least one year at this meat processing plant and in the meantime, apply for permanent residency (i.e., a “green card”) for him and family to ultimately stay in the U.S. permanently. If everything goes according to plan, Bao will have to pay the labor recruiter around $40,000 by the end of this whole process.

Personally, I am a little skeptical at the legitimacy of this arrangement and have my suspicions that it may be a scam. I recently spoke to an immigration attorney who said that while the fees that this labor recruiter is charging are very high, this labor certification process is legitimate and if my cousin Bao is able to obtain such a certification, it could be a successful method for him and his family to immigrate to the U.S. But there are a lot of “ifs” along the way and many points within this plan where everything could fall apart and Bao would have basically no recourse whatsoever.

Nonetheless, I certainly cannot fault Bao for trying everything he can to leave Viet Nam. He too is aware of the multitude of barriers that he and his family would face if and when they come to the U.S. But his desire to leave Viet Nam is so strong that he is willing to endure all of these challenges so that his children can have a chance at a better life.

So on this anniversary of the Fall of Saigon and as I reflect on my life in the intervening years, I am reminded of the events and emotions that took place 40 years ago — the desperation and resilience of so many Vietnamese to leave for a better life for themselves and their families — and I see that these emotions and desires are still as strong today as they were back then. I also see that life can change in a split second and can lead to such dramatically different outcomes.

Within all of this, I am also very happy for being both Vietnamese and being able to draw on this history and community of strength and resilience, and to also be American and being in a nation that, despite its ample problems and shortcomings, is still the destination of choice for billions of people all around the world.